Fiction, non-fiction, and fact finding…

I read a lot of non-fiction in addition to genre fiction, and I consider myself a lifelong student of history as well as being well-versed in current events. Non-fiction books should always be fact-checked. What about fiction books? And who’s responsible for the fact-checking?

Ultimately publishers and authors are both responsible for fact-checking. Both share the royalties for their books. Publishers often say it’s the responsibility of the authors, that they don’t have the staff to do it. The authors do?

I used to comment on current events in this blog. In those blog posts, I was both publisher and author. Fact-checking was on me. I don’t have any staff, but I fact-checked a lot. It took a lot of time. That’s why I stopped writing those op-ed-style posts. I can commiserate with authors and publishers. It takes time to fact-check. But it must be done.

So much for non-fiction where there’s no doubt that fact-checking is necessary. But what about fiction? A lot of it, especially historical fiction, takes historical events and builds a story around them. From Fred Forsyth’s Day of the Jackal to Dan Brown’s The Da Vinci Code, even mystery and thriller novels use historical facts to give human substance to a story. Forsyth’s facts about the Algerian war were few but correct; Brown’s were invented, not by him, but by others, hoaxes he bought into. Forsyth’s were never questioned, probably because he was a journalist who believed in facts. Brown’s only sin probably was swallowing a bunch of inventive hearsay, and that was only discovered after his book was published.

I’m not even going to discuss more recent and egregious circumstances that have scandalized the reading and writing public. Some authors and publishers have taken a lot of heat, to say the least. Of course, if neither one fact-checks, who will? Politicians are often fact-checked by the media, and occasionally the media checks books to. But with thousands of books published every month, checking every book is as likely as my inventing antigravity.

What can readers and writers do? The important actions are vigilance and skepticism. Both readers and writers can practice those.

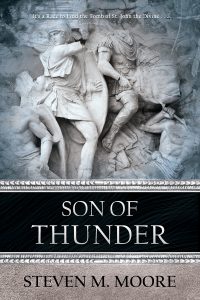

When I wrote Son of Thunder (see below), I was skeptical about many events, especially dating from the time of St. John the Divine. I had the Renaissance artist Sandro Botticelli express some of that skepticism. But I portrayed both the “facts” that I could find, often checking multiple sources. I also tied them together with legend and my own storytelling, a common procedure in historical fiction. But, like Dan Brown, I might later learn there are unintentional gaffes. Historians are welcome to point them out to me; so are readers. I’ll acknowledge that new information, first in this this blog and then in any following editions of the book.

Fact-checking is especially important for the science and technology used to underpin sci-fi. For example, I have a gaffe in common with Andy Weir, author of The Martian. His storm at the beginning of that novel couldn’t do the damage because of the low atmospheric pressure on the Red Planet; the shuttle landing in my More than Human: The Mensa Contagion is equally improbable. We both misrepresent the Martian atmosphere. In Rembrandt’s Angel, I described a BMW as a British motorcar. I knew better—it’s German, of course—but I had been reading analysis of BREXIT’s consequences. One was the that BMW parts, many made in the UK, might have to be made elsewhere when UK leaves it. In the book, BREXIT has already occurred, so that might end up being a gaffe too!

The farther we go forward in time and the farther we go back, the less we’re certain about facts. The former is often extrapolation, the wilder the time lapse. The latter is due to legend being confused with history and just the lack of hard facts. Readers and the media can keep authors and publishers honest; and authors and publishers must police themselves the best they can. That’s all hard to do with the number of books that are published every year!

***

Comments are always welcome.

Son of Thunder. Art detective Esther Brookstone, now retired from Scotland Yard, becomes obsessed with finding St. John the Divine’s tomb using directions left by the Renaissance artist Sandro Botticelli. Esther’s search, the disciple’s missionary travels, and Botticelli’s trip to the Middle East make for three travel stories that all come together in one surprising climax. Esther’s paramour, Interpol agent Bastiann van Coevorden, has problems with arms dealers, but he multitasks by trying to keep Esther focused and out of danger. The reader can also learn how their romance progresses, as well as travel back in time to discover a bit about Esther’s past with MI6 during the Cold War. Available in print and ebook versions at Amazon and the publisher, Penmore Press, as well as in ebook versions at Smashwords and its affiliated retailers (iBooks, B&N, Kobo, etc.). Or visit your favorite local bookstore (if they don’t have it, ask for it).

Around the world and to the stars! In libris libertas!