Car, train, ship, or plane?

Inspiration for this post doesn’t come from the Fast and Furious franchise or the new Matt Damon movie, Ford vs. Ferrari. It’s about the relationship between settings and conveyances.

A love affair with cars is much more muted in Europe than in the US. Sure, Europeans love fast cars—just try to drive on the Autobahn sometime, or on those UK and Irish back roads—but trains play a more important role. As a young traveler in frugal tourist-mode before and after conferences, I’d buy a Eurorail pass. Sleeping on the train to avoid hotel costs and waking up in a new European city or even country let me see a lot of Europe, at least the part outside the Iron Curtain (you’ve already read about some of my experiences in ex-Iron Curtain countries, which are much more recent). Train travel around Europe is easy, and it’s the way a lot of Europeans travel. As an author, you can neglect this cultural tradition at your own peril if your story is set in Europe. Even those opening scenes in Goldfinger made that mistake as the film’s directors pandered to American audiences—the villain’s Rolls Royce was still a car, after all, and James Bond’s famous Aston Martin was a fast car. (When I saw From Russia with Love, I thought, “How appropriate! Bond’s on a train.” Or was that The Spy who Loved Me?)

Traveling is part of culture in the US and abroad. A lot of us in the States like to get from point A to point B fast. “Fast” is always a bit of a stretch when we add on commuting time to airports, traffic in airports, and airline delays, whether due to weather (can’t control that) or faulty maintenance of the aircraft, cancellations, or TSA security (something should be done about those). I found train travel in Europe a welcome respite from European plane travel, but not so much in the US (once a strike by Allitalia when I wanted to fly from northern Italy to Madrid didn’t add to my appreciation for European plane travel—I had to go the long way around, back to Rome and then on to Madrid). For one thing, the US is just too big. For another, the options for train travel are minimal.

Car travel is different—more personal, less costly in general, and more dangerous, statistically, the danger directly proportional to speed as well as traffic density, no matter how many safety features the car has. Touring is also an easy way to see more countryside—train tracks are fixed and planes fly only between certain cities and fly so high that you can see very little.

The mix in Europe is a bit more logical and better than in the US. Eisenhower didn’t help with his gift to US auto manufacturers, the creation of the interstate highway system, but the dominance of car travel in America would probably have occurred anyway. Americans love cars and often see them as a status symbol. Europe is more compact and geared to offer travelers all options, including ferries to carry their cars and trains and ships cruising between various ports.

The US used to be more into trains and ships. The easiest way to Gold Rush Country in California (I’m looking at one of my father’s paintings of an old building from the area where gold was discovered) was by ship around the tip of South America (not so easy even by today’s standards, and you can do it via the Panama Canal). Once that golden spike was hammered into place in the cross-country railroad, trains connected the East Coast to the West, and vice versa (again, not so easy or fast, but the car didn’t exist at the time).

Train travel lost importance with the advent of air travel, no matter the size of some countries. When I lived in Colombia, that was obvious. Trains never took hold there in that mountainous country. Car travel through mountain passes and jungles was iffy and fraught with danger, especially during the ELN and FARC’s heyday. Colombia, with three subchains of the Andes running through it, became a modern country, its wonderfully diverse regions connected, when plane travel between its cities became common.

Again, Europe’s logical mix has a long tradition. LA and other American cities are polluted by car emissions, although they’re improving. I don’t know of any European city that has ever had that problem. (We can’t count Russia with its tradition of ignoring destruction of the environment and greenhouse gases as an European country—it’s always been more Third World. It’s surprising that Moscow isn’t as badly polluted as Sao Paulo or Mexico City.)

Transportation choices are part of a country’s culture. They are often traditional choices of that country’s citizens, but they can be warped and misguided by acts of a country’s government. All that factors into fiction with its plethora of possible settings, which should be as realistic as possible. An American might not know about other options for going from DC to Boston…or care. It’s rare that an Englishman doesn’t know about them for going from London to Manchester. That’s a cultural difference to consider in our fiction when we create settings for our stories.

***

Comments are always welcome.

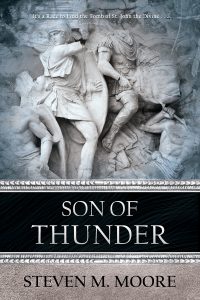

Son of Thunder. Ex-Scotland Yard Inspector Esther Brookstone obsesses about finding St. John’s tomb following directions in the frame of a painting by Renaissance artist Sandro Botticelli that she appraises. Or is she trying to prove the famous painter was never in the Middle East? Part of her search is via a long train ride to Ephesus, Turkey. That might remind you of Christie’s Murder on the Orient Express. Even though wags call Esther Miss Marple and her boyfriend, Bastiann van Coevorden, Hercule Poirot, the modern crime-fighting duo doesn’t solve a murder on the train. Instead they’re unsuspecting participants in a race to find the tomb. Available in print and ebook versions on Amazon and from the publisher, Penmore Press, and in ebook versions from Smashwords and all its affiliated retailers (iBooks, B&N, Kobo, etc.). Also available at your favorite local bookstore (if they don’t have it, ask them to order it for you).

Around the world and to the stars! In libris libertas!