Provincialism and nationalism…

The –isms are often thought of as political or religious: conservatism, progressivism, Protestantism, Catholicism, Buddhism, and so forth. The –isms in the title often mingle with those first –isms, but they can also appear in fiction. A lot of Steinbeck stories are examples of provincialism, for example, that of California’s middle coast area around Stockton. The US is so large that provincialism naturally occurs as varying regions become settings for a novel. Harper Lee’s To Kill a Mockingbird is provincial. Even genre fiction—Michael Connelly’s Harry Bosch series, for example—is provincial for the most part (I think Harry leaves the LA area in one book to go to China, though).

One can argue that American readers want provincial or national—DC is often a setting for a political thriller, for example. There’s something familiar and comfortable about regional and national settings. Let’s call these readers “comfort readers”—I don’t mean anything pejorative by using that description; it’s a reading choice.

There are other readers who want to explore new places, even places far away from Earth! They might still want to be comfortable in those strange settings, or want the author to make them feel comfortable in them. But some also want to feel threatened by a hostile government to empathize with the protagonists of the novel. Let’s call these readers “experience-seeking readers.”

Finally, there’s a class of readers who are a bit masochistic. They like “raw” stories of violence and horror, especially if it occurs in setting they’re familiar with. Dean Koontz and Stephen King are old masters who appeal to this group, with Dean being a little more mature in his storytelling than Stephen. Let’s call these readers “masochistic readers.”

I repeat: I don’t mean anything pejorative by choosing these names for these classes, nor do I claim they’re the best names—you might have better ones. Moreover, what’s curious to me is that these sets aren’t disjoint. Readers are a bit like hummingbirds, flitting from flower to flower in their reading. (I probably shouldn’t call books appealing to readers in that third class flowers—my metaphor is a wee bit flawed—but they’re flowers in the sense that many are quite good.)

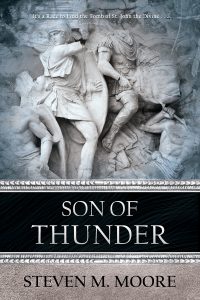

I certainly skip around a bit in my own reading and writing. In Isaacson’s Leonardo da Vinci, I found that Florentine setting as interesting as Leonardo’s life; it influenced my writing of Son of Thunder (see below). For an Italian, that book is provincial; for me, as an American, I was in that second class of readers as I read it—I was exploring Renaissance Florence in a way I never could by visiting (I visited the 20th century version once). I had a similar experience reading Carole Lawrence’s Edinburgh Twilight; 1880’s Edinburgh is different than the 20th and 21st century Edinburgh found in Ian Rankin’s books. In other words, readers in my three classes can experience settings that span the entire four-dimensional continuum of space and time.

These distinctions go far beyond genre. Even additional adjectives like historical, archaeological, and so forth are just keywords we can use to describe books readers read and writers write. These keywords express commonalities. I prefer to think of every book as unique (even though I committed the sin of creating those additional classes above!). The great adventure lies in discovering their differences! Saying one book is like other books is not necessarily a good promotional tool either, because readers might not like some of those other books. The mere fact that readers often read books from all three classes indicated above means reading tastes are fluid. And that’s wonderfully human!

***

Comments are always welcome.

Son of Thunder. #2 in the “Esther Brookstone Art Detective Series,” this sequel to Rembrandt’s Angel has Esther Brookstone, now retired from Scotland Yard, obsessed with finding St. John the Divine’s tomb, using directions left by the Renaissance artist Sandro Botticelli. Esther’s search, the disciple’s missionary travels, and Botticelli’s trip to the Middle East make for three travel stories that all come together in one surprising climax.

Esther’s paramour, Interpol agent Bastiann van Coevorden, has problems with arms dealers, but he multitasks by trying to keep Esther focused and out of danger. The reader can also learn how their romance progresses, as well as travel back in time to discover a bit about Esther’s past with MI6 during the Cold War.

History, archaeology, romance, religion, and art make for a tasty stew in this moving, moralistic mystery/thriller novel published by Penmore Press. Available in print and ebook formats at Amazon and from the publisher, and in ebook format at Smashwords and the latter’s affiliated retailers (iBooks, B&N, Kobo, etc.) and lenders (Overdrive, etc.). (The print version might be slightly delayed.)

Around the world and to the stars! In libris libertas!

October 13th, 2019 at 6:17 pm

This was an interesting post. I stay away from Koontz and some of Stephen King’s darker stories because they scare me and put me in a down mood. I like King’s stories like Shawshank Redemption, but not the darker ones. You do a good job of keeping your blog up. Not many of us do not.